Big data analytics and I have had our first personal run-in. Last year, I wrote and spoke about the risks of big data analytics errors and the impact on individuals' privacy and their lives. Recently, I observed it happening in real time... to me! One of Lexis's identity verification products confused me with someone else and the bank trying to verify me didn't believe I am I. I was asked three questions, supposedly about myself; the system had confused me with someone else, so I didn't know the answers to any; and the bank concluded I was a fraud impersonating myself!

Here's how it played out. I was on the phone with a bank, arranging to transfer the last of my mother's funds to her checking account at another bank. The customer service representative had been very helpful in explaining what needed to be done and how. I have power of attorney, so have the right to give instructions on my mom's behalf. However, before executing my instructions, the representative wanted to verify that I am who I claimed to be.

In the past, companies confirmed identities by asking me to state facts that were in their own records - facts I had provided, like address, date of birth, last four of Social Security Number. Instead, the representative informed me, he would be verifying my identity by asking me some questions about myself from facts readily available on the internet.

The good: That's a pretty reasonable concept. The typical personal identifiers have been used so much that it's getting progressively easier for other people - bad guys - to get access to them. In a 2013 Pew survey, 50% of people asked said their birthdate is available online. The newer concept is that there are so many random facts about a person online that an imposter couldn't search their way to the answers at the speed of normal questions and answers.

The bad: The implementation doesn't always match the concept. The customer service representative asked me "What does the address 7735 State Route 40 mean to you?" Nothing. I later Googled to find out where this is; I don't even know the town.

"Who is Rebecca Grimes to you?" To me, no one, I don't know anyone by that name. "Which of the following three companies have you worked for?" I had never worked for any of the three companies with very long names. I explained that I lead a relatively public life, that he could Google me and see that I'd worked at IBM, JPMorgan, etc. That might have been my savior, because next he patched in someone from security to whom I could give my bona fides. With my credentials in this arena, a google search, and answering the old fashioned questions, the security staffer told the customer service rep he was authorized to proceed.

The ugly: The rest of the population is not so lucky. They can't all talk their way past customer service or play one-up with the Information Security staff. And, big data has some pretty big problems. In 2005, a small study (looking at 17 reports from data aggregators ChoicePoint and Axciom and less than 300 data elements) found that more than two thirds had at least one error in a biographical fact about the person. In that same year, Adam Shostack, a well regarded information risk professional, pointed out that Choicepoint had defined away it's error rate by only considering errors in the transmission between the collector and Choicepoint, thus asserting an error rate of .0008%.

Fast forward, Choicepoint is gone, acquired by LexisNexis in 2008. My particular problem, the bank InfoSec guy told me, was coming from a Lexis identity service. In 2012, Lexis Nexis claimed a 99.8% accuracy rate (0.02% error), but I was skeptical given the ways accuracy and error can be defined.

The problem, though, is larger. At the end of 2012, the Federal Trade Commission did a larger study (1,001 people, nearly 3,000 reports) of credit reporting, another form of data aggregation and one that typically feeds into the larger personal data aggregators. That study found that 26% of the participants found at least one "material" error, a mistake of fact that would affect their credit report or score. One in four people found a credit-related error. The FTC did not count other factual errors but this provides a sense of the scale of error still being seen today.

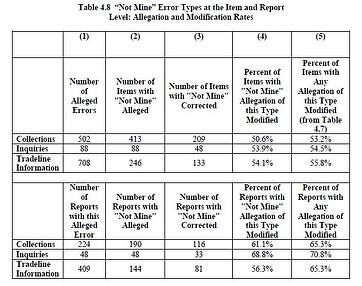

In the FTC study, approximately 20% of the participants sought a correction to their report and 80% of those got a report change in response. About 10% of the overall participants saw a change in their credit score. Appropriate to today's blog topic, the report table above shows that data vendors agreed with more than 50% of the complaints that they'd mixed in someone else's data.

The individual today has the choice between regularly chasing after big data analytics errors or suffering the consequences of mistaken beliefs about themselves. Some very prominent folks in the Privacy policy sphere have told me this isn't a privacy issue. I think they're wrong. The Fair Information Practices, which have been in use since the 1970's and form the basis for much of the privacy law and policy around the world, include the requirement that those entitites handling personal information ensure that it is accurate. How much sense would it make if you have a privacy right to keep people from using accurate data in harmful ways, but no privacy right to keep them from using inaccurate data in the same harmful ways?